The History Of The Coconuts

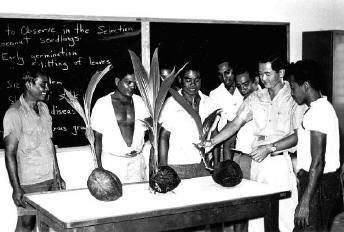

You can probably guess these people live in the tropical countries where the coconut tree is intertwined with life itself, from the food they eat to the beverages they drink. Household utensils, baskets, cooking oil, furniture, and cosmetics all come from the coconut tree.

On the other hand, the uses of the family cow pale by comparison. Like a message in a bottle floating across vast oceans, the coconut, drifting along like a buoyant little ship, was a great traveler riding the waves that carried it ashore in Southeast Asia, Polynesia, India, the Pacific Islands, Hawaii, South America, and Florida. Self-contained hardy souls, many coconuts actually began to sprout during their long ocean voyage. When they found fertile soil in the tropical countries where they washed ashore, they took root and began to grow.

Like a message in a bottle floating across vast oceans, the coconut, drifting along like a buoyant little ship, was a great traveler riding the waves that carried it ashore in Southeast Asia, Polynesia, India, the Pacific Islands, Hawaii, South America, and Florida. Self-contained hardy souls, many coconuts actually began to sprout during their long ocean voyage. When they found fertile soil in the tropical countries where they washed ashore, they took root and began to grow.

Coconut Background History

Some historians surmise that many of the tropical regions where coconuts presently grow received their first coconut trees via the sea. Others believe the coconuts were brought to the different regions of the tropics by explorers and sea travelers. Today coconut cultivation encircles the globe between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn.

Exactly where coconuts originated is not known for sure, but many historians believe Malaysia and Indonesia grew the world’s first coconuts. The conjecture is that early sea travelers of the East Indies carried coconuts with them for nourishment as well as to trade for other commodities.

Early Sanskrit writings reveal that the people of India were using coconuts as a staple for food and various everyday needs. In India, the coconut palm was known as kalpa vriksha, which translates as “tree that gives all that is necessary for living.”

Historians of Zanzibar question whether coconuts are indigenous to East Africa. Based on the fact that similar varieties grow in Southeast Africa and Madagascar, they speculate the coconut did indeed originate in East Africa. An alternative theory is that either seaman from Malaysia brought the coconuts to East Africa during the early centuries CE or Arabian sea travelers who traded crops brought the coconuts from India about 3,000 years ago.

Coconuts made a strong impression on Venetian explorer Marco Polo, 1254 to 1324 CE, when he encountered them in Sumatra, India, and the Nicobar Islands, calling them “Pharoah’s nut.” The reference to the Egyptian ruler indicated Polo was aware that during the 6th century Arab merchants brought coconuts back to Egypt probably from East Africa where the nuts were flourishing.

Zanzibar historians note that Arab traders carried coconut shells, known as Nux Indica, to England before Portuguese sailors reached East Africa. Arab sea travelers discovered profitable goods like cowrie shells and coconut products in the Maldives, islands just southeast of Sri Lanka. There, possibly during the 14th century, they also engaged the Maldives, who was highly regarded for their shipbuilding skills, to build vessels that they did entirely out of products of the coconut tree including the hulls, masts, ropes, caulking, bailers, and even sails.

Zanzibar historians note that Arab traders carried coconut shells, known as Nux Indica, to England before Portuguese sailors reached East Africa. Arab sea travelers discovered profitable goods like cowrie shells and coconut products in the Maldives, islands just southeast of Sri Lanka. There, possibly during the 14th century, they also engaged the Maldives, who was highly regarded for their shipbuilding skills, to build vessels that they did entirely out of products of the coconut tree including the hulls, masts, ropes, caulking, bailers, and even sails.

Had it not been for the curiosity of Antonio Pigafetta, a nobleman from Venice who decided to explore the world as a tourist, Ferdinand Magellan’s voyage from Spain in 1519 might have gone unrecorded. Pigafetta boarded one of Magellan’s five ships and kept a daily journal of his captain’s effort to find a western route to the Spice Islands.

Magellan encountered a host of troubles, mainly scurvy, and starvation. The last resort decision to go ashore when they spotted the island of Guam brought them more troubles. Unfriendly natives wearing coconut shell masks and shaking coconut shell rattles with human bone handles greeted them on the shore. Magellan was able to negotiate and came away with provisions and a good supply of coconuts.

Pigafetta wrote, “Coconuts are the fruit of the palm trees. And as we have bread, wine, oil, and vinegar, so they get all these things from the said trees. . . With two of these palm trees, a whole family of ten can sustain itself. . . They last for a hundred years.”

Not long after Magellan’s voyage, Sir Francis Drake journeyed from England to the Cape Verde Islands off Africa’s West Coast in 1577. He, too, was impressed with coconuts and wrote, “Amongst other things we found here a kind of fruit called Cocos, which because it is not commonly known with us in England, I thought good to make some description of it.”

Not long after Magellan’s voyage, Sir Francis Drake journeyed from England to the Cape Verde Islands off Africa’s West Coast in 1577. He, too, was impressed with coconuts and wrote, “Amongst other things we found here a kind of fruit called Cocos, which because it is not commonly known with us in England, I thought good to make some description of it.”

Though the accounts of many explorers mention coconuts, the nuts remained unknown outside their tropical habitats until 1831 when J.W. Bennett, an Englishman, wrote A Treatise on the Coco-nut Tree and the Many Valuable Properties Possessed by the Splendid Palm. Revelations such as applying charcoal from the shell as a tooth cleanser, removing wrinkles with coconut water, and using the root for medicinal purposes spurred European interest in the nut.

Since sugar was becoming plentiful on the continent, the candy and pastry business blossomed. All sorts of fruits and nuts were incorporated into confections, making coconut meat a desirable product. Soon tea and spice traders were shipping whole coconuts to London, an operation that proved impractical and expensive.

A French company, J.H. Vavasseur and Company, set up operations in Ceylon with a unique solution for shipping coconuts to Europe. They shredded the coconut meat and dried it thoroughly, making it easier to pack without spoilage. By the early 1890’s they were shipping six thousand tons of desiccated coconut, a figure that multiplied by ten in 1900.

While Europeans were going nuts over coconuts, interest in the United States hardly produced a nod until 1895 when Franklin Baker, a Philadelphia flour miller, received a shipload of coconuts in payment of a debt from a Cuban businessman. After a few unsuccessful attempts to sell the enormous cargo before the nuts spoiled, he made a decision that put coconuts into the hands of home cooks, commercial confectioners, and pastry chefs alike. He set up a factory for shredding and drying the coconut meat.

By the early 1900’s, coconut cream pie and coconut custard were the rage. Coconut frosting topped all sorts of cakes, while grated coconut added its distinct aroma and flavor to cookies and confections.

Today, coconut plantations in Indonesia, Malaysia, India, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines provide export income to these regions. The United States has imported its coconuts mainly from the Philippines since 1898 when the islands became a U.S. possession at the end of the Spanish-American War.

Zanzibar, an island off the East coast of Africa, depended on coconuts for food and as a cash crop for centuries. Natives used twisted cord made from the coconut husk to stitch together the hulls of boats that sailed the Indian Ocean.

From past centuries to the present, the nuts are considered survival food, sustaining communities after major tropical storms destroy the rice paddies or cornfields. Before 1950, about 60 percent of the coconuts were shipped to the United States to be shredded and dried. After that time the coconut producing countries shipped the coconut meat already grated and dried.

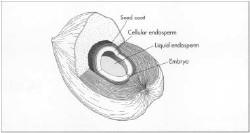

Coconuts come to market in two major stages of maturity. Young coconuts are prized for their sweet, revitalizing juice. The meat of the young coconut, which is very thin, soft, and delicately sweet, is gaining interest among innovative raw foodists who turn it into imitation noodles and other delicacies.

The mature coconut is valued for its thick, firm meat used world wide in shredded or grated form, often for baked goods. Coconut in its mature stage has a rich, nutty flavor and chewy texture with a higher oil content than young coconut. Coconut milk, coconut cream, and coconut oil all come from mature coconuts. (Buy Coconuts From Our Cooky Coconut Store)

The Coconut Gets its Name

Spanish and Portuguese explorers were taken by the three little eyes at the base of the coconut’s inner shell that reminded them of a goblin or grinning face, and named them coco, the word for goblin. Some have translated the word coco to mean monkey face.

Spanish and Portuguese explorers were taken by the three little eyes at the base of the coconut’s inner shell that reminded them of a goblin or grinning face, and named them coco, the word for goblin. Some have translated the word coco to mean monkey face.

Published in 1755, Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language spelled the fruit cocoanut. Many people thought Johnson had confused the nuts with the cacao beans, later called cocoa, when chocolate was introduced into England. Eventually, the “a” was left out. Sometimes it was spelled with a hyphen–coco-nut.

Coconuts’ Many Uses

Considered the most useful tree in the world, the coconut palm provides food, drink, clothing, shelter, heirloom history, and financial security. Hardly an inch of the coconut palm goes to waste in countries such as the Philippines where families rely on the coconut palm for survival and refer to it as the “tree of life.” The Indonesians say, “There are as many uses for the coconut as there are days in the year.”

The coconut meat, the white portion of the nut, offers more than just sustenance. The coconut is considered a highly nutritious food. The white meat also contains coconut oil the tropical natives use for cooking.

The shell, husk, roots of the tree, fronds, flowers, and wood of the trunk also become useful products. Charcoal filters used in gas masks and cigarettes are made from coconut shells that are burned, leaving pure carbon behind. Charcoal has the ability to trap microscopic particles and impurities and prevent absorption. Charcoal made from coconut shells produces filters of exceptionally high performance.

One-third of the coconut’s make-up is the hairy husk that is soaked in saltwater until it is soft enough to spin into rope or twine that is known for its durability. The rope, called coir but pronounced coil, is highly resistant to saltwater and does not break down like other fibers including hemp.

The coconut husk has household practicality in tropical countries where coconuts are part of almost everyday cuisine. The husk provides fuel for cooking as well as fiber for making clothing.

Coir is also used to make mats. Another byproduct of the coconut husk is coir dust used in making fertilizer and plastic-board insulating material.

Travelers to tropical countries find a host of native crafts woven from the fronds of the coconut palm into hats, baskets, fans, brooms, little animals, belts, and chairs. In the past natives even wove the roof thatch of their homes from coconut palm leaves. Coconut tree roots were also put to practical use by boiling them down to create a dye.

In Zanzibar, coconut oil provides diesel fuel and is also used for lighting and candle making. Coconut shells are made into buttons, form a base for decorative carvings, and are burned for fuel.

Indonesian women use coconut oil as hairdressing and as a lotion for the body. They also cook with coconut oil.

Coconut oil has proved itself useful in many household products. Soap made from coconut oil lathers exceptionally well. Soapmaking produces byproducts that are used by processors to make fatty acids and glycerine.

Coconut oil is often included in shampoo recipes as well as shaving creams for its excellent moisturizing ability as well as its ability to produce abundant lather. The cosmetic industry incorporates coconut oil in the manufacture of lipstick, suntan lotion, and moisture creams.

The coconut shell serves as a bowl or cup and can be carved into other household items such as spoons, forks, combs, needles, and handles for tools.

Finally, when the tree is no longer producing coconuts, it can be cut down and its attractive wood, called “porcupine wood” can be used to make furniture.

Folklore and Oddities

From fertility taboos to unseen magical forces, fascinating folklore practices revolving around the coconut have evolved throughout the tropical regions .

Until the early 1900’s, a whole coconut was the accepted form of currency in the Nicobar Islands, just north of Sumatra in the Indian Ocean. In the South Pacific, pieces of coconut shell carved into coin-like spheres served as currency.

In Northern India, coconuts were valued as fertility symbols. When a woman wanted to conceive, she would go to a priest to receive her special coconut.

Samoans believe that a coconut lying on the ground is not free for the taking but that it belongs to someone who knows it is there. If you should claim the taboo coconut when no one is looking, the tapui, a magical spirit, will taunt you. This unseen force may strike you by lightening or punish you with a painful, incurable illness.

The first solid food eaten by a Thai baby is three spoonfuls of the custard-like flesh of young coconut fed to him or her by a Buddhist priest.

Natives of New Guinea have their own version of the coconut’s origins. They believed that when the first man died on the island, a coconut palm sprouted from his head.

In Bali, women are forbidden to even touch the coconut tree. Because females and coconut trees both share the ability to reproduce, men fear that a woman’s touch may drain the fertility of the coconut tree into her own fertility.

(Buy Coconuts From Our Cooky Coconut Store)

Health Benefits

Indigenous people of tropical countries relied on natural plants for their medicine. Young coconut juice is literally a well-supplied medicine chest that comes in its own container and is used in folk healing for a number of ailments: relieving fevers, headaches, stomach upsets, diarrhea and dysentery. The juice is also given to strengthen the heart and restore energy to the ill. Pregnant women in the tropics eagerly drink large quantities of young coconut juice because they believe it will give their babies strength and vitality

Water from a young coconut not only provided a refreshing drink in the steamy equatorial countries but in times of medical emergency, it was used as a substitute for glucose. During World War II young coconut water became the emergency room glucose supply when there was no other sterile glucose available. Within a clean self-contained vessel, the coconut water is free of impurities and contains about two tablespoons of sugar.

Jon J. Kabara, Ph.D, Professor Emeritus from Michigan State University, writes, “Never before in the history of man is it so important to emphasize the value of lauric oils. The medium-chain fats in coconut oil are similar to fats in mother’s milk and have similar nutriceutical effects.”

Coconuts and their edible products, such as coconut oil and coconut milk, have suffered from the repeated misinformation because of a study conducted in the 1950’s that used hydrogenated coconut oil. Though coconut oil is very high in saturated fat, namely 87 percent saturated, in its unrefined, virgin state, it is actually beneficial, largely because of its high content of lauric acid, almost 50 percent.

Because lauric acid has potent anti-viral and anti-bacterial properties, recent studies have considered coconut oil as a possible method of lowering viral levels in HIV-AIDS patients. The lauric acid may also be effective in fighting yeast, fungi, and other viruses such as measles, Herpes simplex, influenza and cytomegalovirus.

Because the short-and medium-chain fatty acids of extra virgin coconut oil and coconut milk are easily and quickly assimilated by the body, they are not stored as fat in the body like the long-chain triglycerides of animal products. Studies have shown that populations in Polynesia and Sri Lanka, where coconuts are a diet staple, do not suffer from high serum cholesterol or high rates of heart disease.

Extra virgin coconut oil used in a study conducted in the Yucatan showed that those who used coconut oil on a daily basis had a higher metabolic rate. Though they regularly consumed considerable quantities of saturated fat, the participants retained a lean body mass. Another facet of the Yucatan study noted that the women participants did not suffer the typical symptoms of menopause.